Since the first diagnosis of heart failure, some ten years ago, medical professionals have routinely heard my symptoms and feelings about my symptoms and batted them back at me with measurements and data.

“I’m sort of breath,” I say.

“But your oxygen level is at 98%,” they say. “You are getting plenty of air.”

“I feel like I’m retaining fluid,” I send back. “It feels like I’m breathing water.”

“Your ankles are not swollen,” they return the lob.

“Seriously, I’m drowning.”

“Your weight is the same.”

“This thing happened,”

“That makes no sense at all.”

Twenty years ago, after I had been in remission from cancer for three years, my doctors rejected my conviction that it was back because I didn’t have the textbook symptoms (fever, night sweats, rash). Also, my blood work was normal, and so was my chest x-ray. Funny thing about tumors in the lower Iliadic chain, they don’t show up on chest x-rays. My gut was telling me I was sick again and my general practitioner prescribed Prozac. Plus, even with my first diagnosis, my blood work was normal and I lacked the textbook symptoms. I get so frustrated when my feelings about this body I have inhabited for 59 years are dismissed because of data and measurements.

As I waited for the time I would be wheeled into surgery for my recent heart valve replacement, my ICU recovery nurse introduced herself and give me an idea of what the hours after my surgery would look like. She told me that, when I woke up, I would be on a ventilator and my arms would be tied down. I would be restricted in my ability to move, and completely unable to communicate. To be honest with you, I almost backed out. The words, “I’ve changed my mind,” where on my lips. I mean, can’t they just leave me unconscious until I can communicate and move?

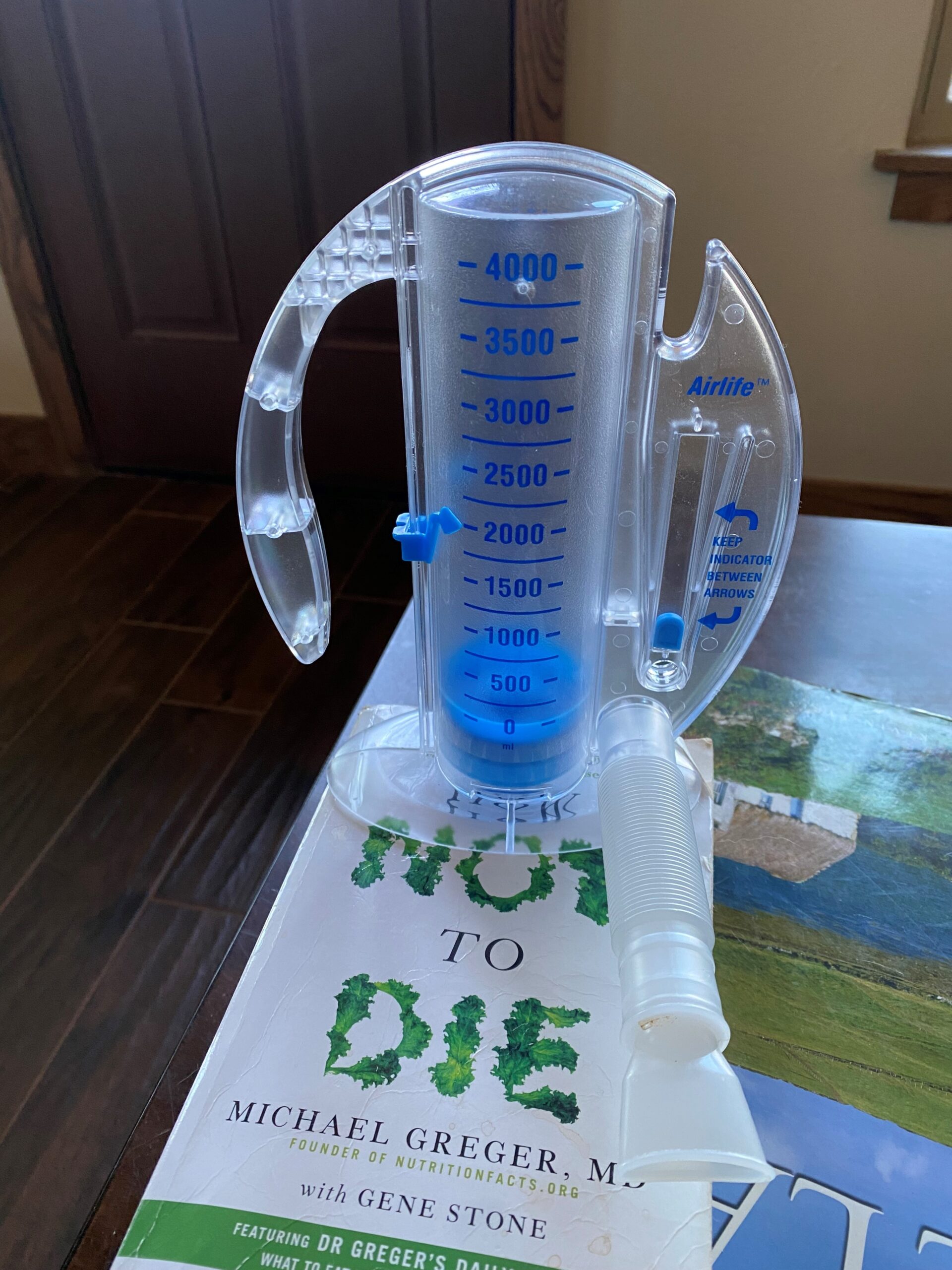

The item in the photo is an “incentive spirometer.” During our introduction, the ICU recovery nurse handed me this very spirometer and asked me to take a slow steady drag from the hose. I was not to let the small bead at the bottom arrow rise above the top arrow; taking too quick a drag would cause that. As I inhaled, the blue disc at the bottom rose and gave them a measurement of my pre-surgery pulmonary function. The blue disc rose to 1500.

“Very good,” the nurse said. She added that after I got off the ventilator I would use the spirometer every day and report back the result to my nurse.

Now, I didn’t know whether 1500 was “very good” or sucky. Before I could get my phone out to Google it, the team arrived to wheel me to surgery. My suspicion was if 1500 was “very good,” the spirometer would not go up to 4000.

True to her word, once the ventilator was removed I was asked to suck on the spirometer again. I was confident my new valve would have improved my pulmonary capacity immediately. Typical me, ignore all the “but it will take time” warnings and go straight to immediate success. I was disappointed when it took all my energy and lung capacity to get above 600, worse than pre-surgery. “No worries,” I was assured things would improve over time. I used that thing anytime I was alone in my room. Some days it would improve, some days it would not. It was hard work, but I felt like I should at least be back at 1500 before I left the hospital. I was concerned they wouldn’t let me go home if the number was lower than when I came in. I was right around 1200 when they discharged me.

“Keep using the spirometer,” the nurse told me as I signed the discharge paperwork. “Use it every day, track your progress.” I did, for awhile, but the progress was so slow and sometimes I couldn’t get much over 1000. Why was I losing ground? So frustrating! I set the spirometer on the bottom shelf of the end table so I didn’t have to look at it. I ignored it for weeks.

Yesterday, my home health nurse asked me if I was still using it. “Sometimes,” I lied to her. But then, “honestly, not lately.” She encouraged me to get it out and use it again.

Today I got to 2000 – more than my pre-surgery number. I launched Google to see if my reading was “normal” or maybe even above normal for someone my age, having heart failure for 10 years and valve replacement. I couldn’t get a clear answer to my question. But, do you know what I did find out? I found out that the incentive spirometer is supposed to be used to increase my pulmonary function over time, not just measure it. It is a tool and an measuring stick. But still the measurements are there and affirm that my pulmonary function is improving. I’m happy for that.

Measurements don’t always show the full picture. Sometimes the patient’s instincts are right. I know it is difficult for doctors to listen to a patient’s complaints when they don’t agree with the data, but I wish more would. My cancer wasn’t textbook, my heart failure wasn’t either. I rarely do anything the way I’m suppose to.

But, the spirometer is back on the table to remind me to use it every day. And I will. Probably.